A lesson in Linz

The non-linear nature of knowledge strikes again.

Linz isn’t the first Austrian city that comes to mind for most, but with a wealth of history, gorgeous architecture, and — not trivially — a surplus of köstlich linzercakes, it's a worthy addition to any itinerary in the region.

Classical music enthusiasts may recognize the name, as Mozart wrote his “Linz Symphony” during a 1783 long-weekend stopover at a crashpad on Altstadt in a building that still stands (and now bears his name).

The center of the old city is compact and walkable. Even a few hours is enough to get a thorough impression. Much of the action revolves around the hauptplatz, which features a 300-year-old baroque statue, a streetcar line down the middle, and an enclosing block of restaurants, coffee houses, hotels, and variety shops.

Five minutes by foot from the main square is a street called Hofberg — a sloping, cobblestoned off-ramp from the historic center to the Eferdinger Straße, which is part of a state highway along the Danube that releases cars from the pre-automobile maze above.

At first sight, a visitor can’t help but notice a four-story building on the street’s western side that, despite having seen better days, looks to have seen many days.

As I paused on the sidewalk, fumbling with the machinery of a new camera, my attention landed on a woman quite suddenly standing to my right. A cursory estimate put her in her 80s, while a more dependable one found her just shy of five feet tall.

Scarf wrapped around her hair, cloth bag over her arm, and cane in hand, she looked every bit the distinguished, purpose-driven Großmutter you’d expect to see on a street like this.

Without greeting or introduction, and in a firm, slow, quiet voice, she started to run through the building's history for this (obvious) first-time visitor; a Cliff's Notes summary of owners, occupants, events, and ghosts from the centuries of its life.

Well... I think so. She spoke in German, of course, which is a language unknown to me beyond the twenty-something words that allow armchair polyglots to order a meal or wish someone well.

Fifteen, then thirty, then forty-five seconds. She kept on going. I smiled and nodded. While Entschuldigung and kein Deutsch are among the words I do know, I couldn’t get them out. She was going to finish the lesson and it wasn’t right to interrupt.

A light dawned, most likely, when she paused for a moment and I said “it’s beautiful” in native-tongue English. It didn’t seem to affect her. Or maybe it just didn’t surprise her. After another few seconds, and what sounded like a variant of “enjoy your time in Linz,” she was on her way — up the slow incline of the street, six inches at a step, cane poking the sidewalk, toward wherever the daily rituals of half a century take her.

Days later, having moved on to another country but still thinking about that encounter, I did what a lot of travelers and writers like to do. I learned something new.

The building at 4 Hofberg is, by local acclaim, the “oldest historically proven house in Linz” with a recorded lifespan reaching back to the thirteenth century.

For at least 300 years it appears to have been property of the Nonnberg Abbey in nearby Salzburg. The identifier Freihaus Nonnberg remains to the present day.

(Nonnberg Abbey went on to be known for other things in the motion picture era.)

It was a tough century for the Freihaus in the 1500s as it underwent its own kind of reformation, first divested by the abbey and then seemingly gutted (or totally rebuilt) under private ownership. By 1650, historians say, the building housed an inn subsequently known as Gasthof zur Weißen Gans.

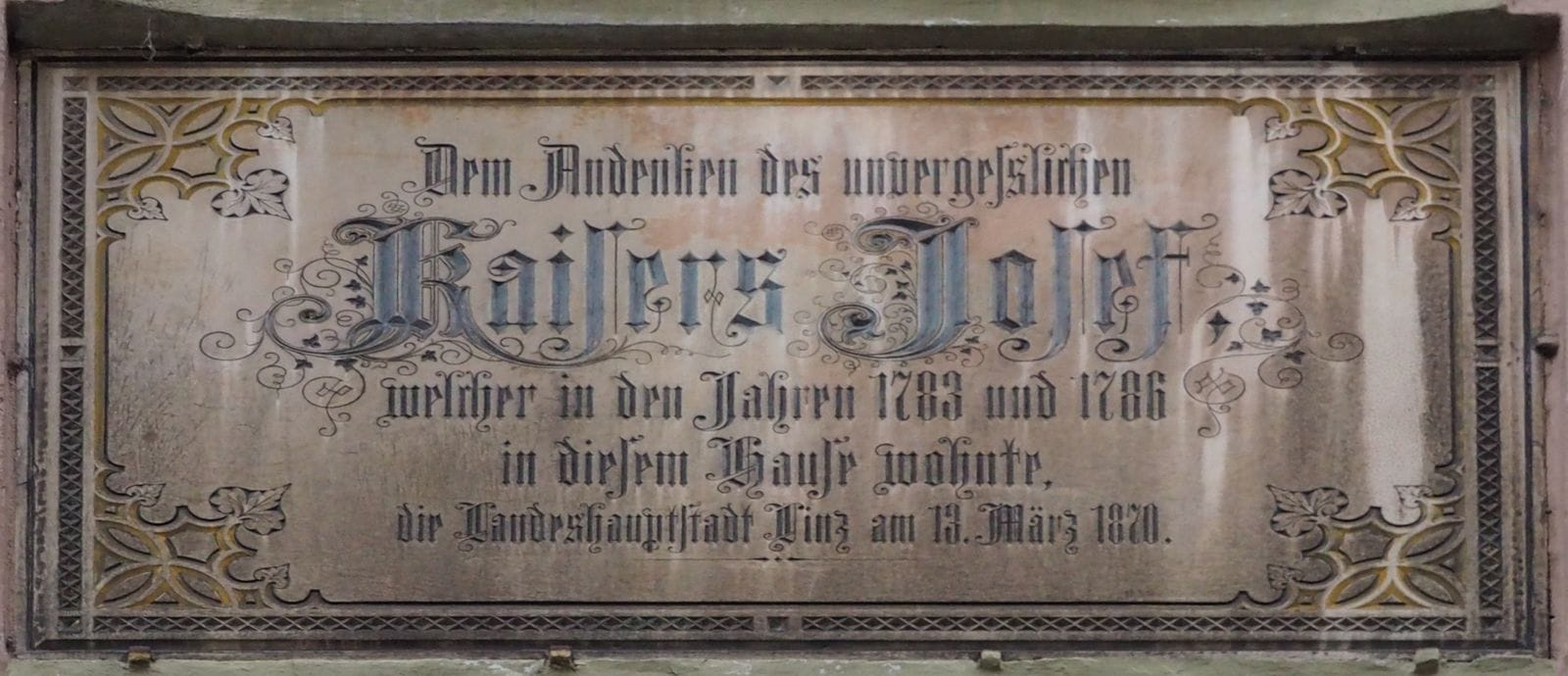

A wearied plaque halfway up the facade notes its record as a residence of Joseph II during his command of the Habsburg monarchy in the 1780s – although it's a bit odd to think of the Holy Roman Emperor settling into a room at the White Goose Inn. A different era, perhaps.

(They say the Kaiser made an effort to “establish German as the sole language of administration and communication” across his empire, so my comprehension struggles outside his old abode surely entertained him if his spirit was nearby.)

The building went through some renovation in the 1950s but there’s little evidence of a full-scale rehab. At least on the outside. All things considered, it’s holding up well enough for its age. It could use some attention, and it’s not quite as sharp as its neighbors, but there’s been enough to pass inspection and forge onward. The street-level bar Nachtschwärmer (“Night Owls”) earns 4.8 stars on Google, so Freihaus Nonnberg continues to entertain guests as its eighth century unfolds.

Looking back, I do wish I knew exactly what that kind woman said. But I remember standing in front of that building with her. I remember her face and her voice. I remember the care and intent with which she addressed a curious, unimportant stranger. And without those moments knocking around in memory, I might not have peeled back the first few layers of that building’s story. Eventually, at least in some measure, I absorbed what she wanted me to know.

Perhaps she shared the lesson perfectly.